For the organisation's second talk of the year, our Vice-Chair, Quintin Watt, will look at fatal transport accidents between 1820 and 1920. In this short excerpt, Quintin looks at some examples from Wolverhampton that will have you reaching for your seatbelt! Details of the event can be found directly below; click the image to reserve tickets.

Introduction

Most of us have witnessed road traffic accidents, or even been involved in them. Sometimes accidents can happen on public transport. Several years ago I managed to fall down the stairs on a Number 1 bus en route from Wolverhampton to Dudley. However, the broken ankle I sustained was insignificant compared with the fates that befell two coach passengers one hundred and ninety years ago. Their sad stories reveal that travelling on public transport ‘in the old days’ was even more dangerous than it can be today!

In the “Box Seat”

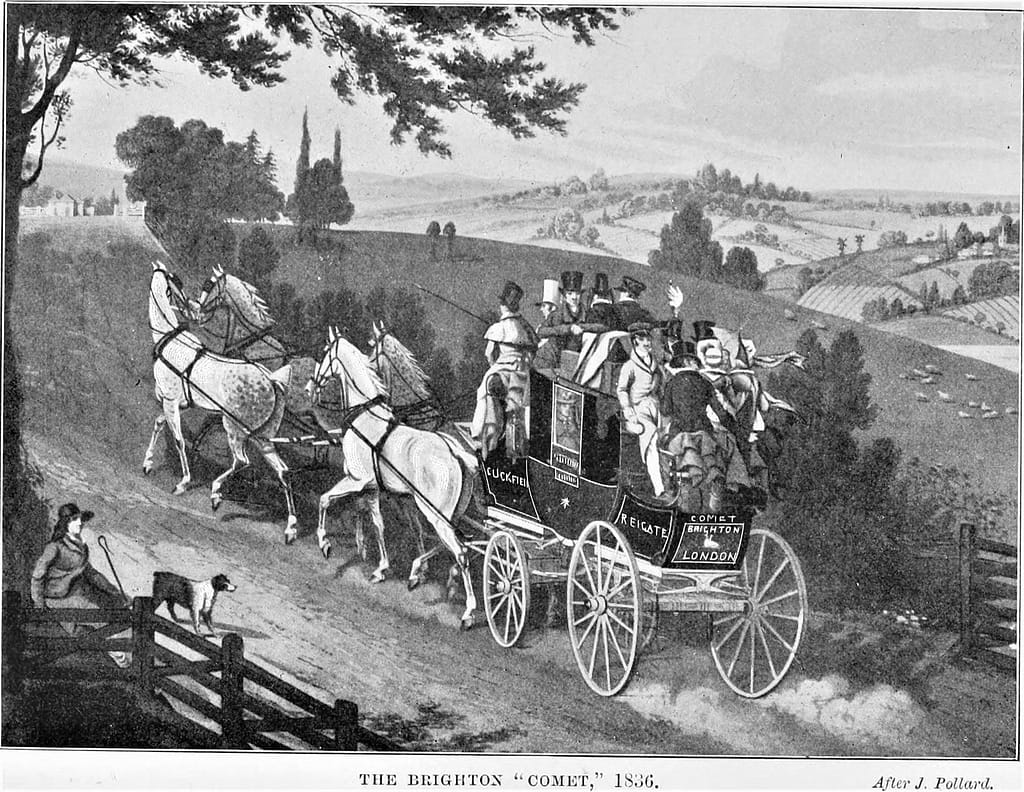

In December 1827 a “most deplorable accident” happened to Mr William Bullock whilst travelling home from Wolverhampton to Stafford on the Liverpool mail coach. This thirty-one year old shoe-manufacturer came to town that Tuesday afternoon to conduct business arrangements. Once completed he returned to the coaching inn and climbed up to sit on the box-seat – so named because it contained the mail – next to the coach driver.

Stage coaches in the 1820s offered passengers a choice of seats; expensive ones inside and cheap ones ‘on top’ in the open air! About two miles into the journey back to Stafford, as the coach was passing through Fordhouses, the coachman complained that Bullock’s “top-coat intercepted the light from the lamps.” Old coach lamps were pretty dim at the best of times and on a December evening their beam must have been pathetic. Thus prompted by the driver, Bullock suddenly stood up to adjust his dress. Unfortunately, he completely lost his balance, fell off the speeding coach, landed in the road and “fractured his neck in a most shocking manner – the head being completely loosened from the trunk!”

Two days later the Coroner’s Inquest, carried out by H. Smith Esq., recorded a verdict of “Accidental Death.” Bullock’s demise was described as “instantaneous”, but he left “a truly inconsolable widow and three little girls to suffer the very serious deprivation of a husband and a father.” One wonders whatever happened to his family in the aftermath of this heart-breaking accident.

Faster Than a Speeding Greyhound

Two years later, on the evening of Friday 28 August 1829, William Edwards was a passenger on The Greyhound Coach. This set off from Wolverhampton to Birmingham along the Bilston turnpike road – the modern A41 – at the heady speed of 7mph.

Why “a young man of very respectable connections” bought a ticket to travel on the top of the coach is unknown, but this fateful decision cost him his life. As the coach reached Monmore Green, about a mile into its journey, catastrophe stuck. Near where the main rail line from Wolverhampton to Birmingham crosses over the road, the front axle of the coach suddenly snapped. One of its front wheels shot off across the road whilst the crippled coach was dragged for another hundred yards before the horses broke free and bolted off towards Bilston.

In the chaos, the five ‘outside’ passengers tried to leap off the coach. Four managed to land safely, but William Edwards was unlucky. He landed on his feet but the momentum carried him so he hit his head on the road and fractured his skull. The poor man was carried into a nearby public house and attended by local surgeon, Mr E.H. Coleman, who rushed to the scene. Despite his best efforts, Edwards expired at 4am the following morning having never regained consciousness.

The Inquest

The Inquest was also conducted by Coroner H. Smith Esq., who had officiated at William Bullock’s, two years earlier. It transpired that Edwards was an assistant in a linen drapers shop in London and was on his way home having visited friends in Oswestry. Coroner Smith took evidence from a range of people incident including Mr Booth the coachman, Mr Sparrow an eye-witness, and Mr Freer a surgeon who examined Edwards’ body.

The Jury reached a verdict of ‘accidental death’ and declared no blame should be attributed to coachman Booth. However, they also laid a “deodand of twenty shillings upon the coach.”

In old English law a deodand was like a financial or material forfeit – originally to be given to God – by something that had caused someone’s death – even an inanimate object. For example, if a person was killed by an escaped bull the Inquest jury could demand the bull’s owner pay compensation to the victim’s family – a deodand based on the value of the animal.

Deodands were eventually abolished by Parliament in 1846 because of increasing numbers of transport-related deaths – not by coaches, but by trains. In the early days of railways people could not judge the speed of locomotives because they have never seen anything that big move at 30mph before! Inquest juries often assigned deodands against railway companies as compensation, based on the value of the train. This lead to claims amounting to thousands of pounds against railway companies many of whose directors also happened to be MPs!

The Mail Must Come First…

A very similar accident to the one that killed poor William Edwards took place in October 1837 when another coach axle broke. This happened when the Shrewsbury and Birmingham mail coach was approaching Wolverhampton along Thomas Telford’s road through Tettenhall. In spite of the “great violence” of the coach’s sudden collapse, none of the passengers was seriously injured apart from suffering a few bruises. Coach proprietor, Mr Jobson of Shrewsbury, appears to have come off worst, being “much cut about the face”. However, the all-important mail had to get through at all costs, and the coach guard “immediately proceeded to Birmingham with the letter bags, in a chaise.” Once another coach had been acquired, the passengers “followed shortly afterwards.”

Sources used:

- The Evening Mail, 5 December 1827

- The Worcester Journal, 3 September 1829

- The Birmingham Journal, 5 September 1829

- The Coventry Standard, 13 October 1837