The Wolverhampton Synagogue is a dimuniative building, but hid a secret to its past for many years. Finally in 2020, the secret was revealed, and from the most unlikely of sources.

Wolverhampton’s Jewish Pioneers

The first Jewish citizen in Wolverhampton arrived in 1834, having made the journey from Kretinga, Lithuania, to Gravesend, Kent two years prior. Levi Harris was a pawnbroker and clothier who would spend the final 21 years of his life living in Wolverhampton. He was clearly well liked by natives, as several signed his attestation papers. At the time, Jews were still not permitted to own property, and Levi had to become a British citizen. He would do so in 1849, and own property in Berry Street and Worcester Street. Whilst he was the first to make the city his home, Levi was joined by a small Jewish presence in the town over the next 15 years.

Humble Beginnings

The congregation was still too small at this time to be able to form a quorum and thus there was no formal synagogue. Ceremonies such as weddings would take place in houses, as evidenced by the 1849 wedding of Philip Goldstein and Goosty Berenstein. The ceremony was performed at an address in St George’s Parade, which was the property of Marcus Gordon at the time. Gordon became a pastor soon after he arrived in 1846 and was one of the key figures within the Victorian-era orthodox community. Levi’s wife, Sarah, was a witness, as was Simon Aaron, another early pioneer. Aaron and Gordon were younger men, both Polish, and would become community leaders after Levi passed away.

The first real place of worship was a house in St James’ Square, and would be declared open on October 16, 1850. Levi Harris was appointed as vice-chair of the Synagogue, with a man called David Lazarus Davis elected as full chair. Davis was a native of Kent, which was home to a fairly sizable population of Jews at the time. It is purely my conjecture at this point, but I suspect there was a connection formed from the two years Levi spent in Gravesend. The Synagogue also appointed Reverend Isaac Barnett as Rabbi. Barnett was a Polish Jew, who had moved up to Wolverhampton from Woolwich, with his wife and three children.

A Place to Rest

The following year would prove to be another milestone year for the Jewish community. The Duke of Sutherland consented to use a piece of his land, known as “the slang at Blakemore” for use as an orthodox Jewish burial ground. Davis was still working as President at this point and wrote a series of letters to the Wolverhampton General Cemetery Company and the Board of Health. The correspondence reveals several things; that the Jews had rejected the option of a separate section at Merridale Cemetery; that they previously had an agreement with Birmingham for burials; and that the rate of burials was estimated to be one per year. The Birmingham burial ground at this time would likely have been the now-abandoned Betholom Row. The new burial ground at Green Lanes (now Thompson Avenue) opened before 25 June, 1851 and the first burial was Benjamin Cohen. Jacob and Caroline Cohen were another set of the earliest arrivals, appearing in the late 1830s and having their first child in 1841. Benjamin was their second son and aged only seven at the time. He is recorded as having died from dropsy hydrothorax, an old term for an edema.

At the other end of the age spectrum, another early burial was the man who was the true pioneer of the community. On 5 November, 1855, Levi Harris passed away at the age of 60. He died at his address in Berry Street, falling victim to T.B. He would never live to see the arrival of the town’s purpose-built synagogue and does not appear to have a headstone at this point in time either.

A Place of Worship

In 1855, the Jewish Chronicle recorded the number of places of worship in Wolverhampton as 1, with 30 sittings. This is higher than Dudley with 10, but much less than Birmingham where there were 360 sittings. With the comparatively small size of the premises at St James’ Square, a purpose-built venue would soon be required for the community.

By 1857, the campaign to build such a place had begun to gather pace. Land had been purchased on the corner of Fryer Street and Short Street and an appeal for building funds was made on the front page of the Jewish Chronicle on August 7, 1857. After several rounds of appeals in the newspaper, sufficient funds were received to enable the opening stone to be laid on Tuesday, 1 June, 1858.

By the time of the opening of the synagogue, the resident Rabbi was now the Reverend Mennasseh Cohen. Originally from Pzydry, Poland, he made his way to the town via Cardiff, but would ultimately make Wolverhampton his home for decades. Reverend Cohen was joined in the service by Reverend Louis Chapman, a reader from Birmingham. The latter appears to be an interesting character; he is referred to as “lax in his duties, sang when he should chant, and was once “violent” at a smart wedding.”

They led the congregation from the existing synagogue at St James’ Square, left onto Horseley Fields, before turning right at Fryer Street. The area would have been very different – a five way junction – and the Chubb building still far from existence.

Celebrations… in Several Forms…

At the site, prayers written by Chief Rabbi, Dr Adler, were read. A silver trowel with an ivory handle was given to J C Cohen, President of the Birmingham synagogue. The gift was inscribed “This trowel, present to J C Cohen, Esq., by the Wolverhampton Congregation, in commemoration of his laying of the foundation stone of the new synagogue:- June 1, 5618.”

After the ceremony, there are two interpretations of events. Both sources agree that the party retired to the Cock Inn, which was next to Levi’s old premises in Berry Street. However, the Staffordshire Advertiser recalls them “drinking tea”, whereas the Jewish Chronicle records “a very substantial repast, given at the expense of the executive of the congregation”. One wonders if the former received an invite.

Further appeals for funding occurred, but construction was swift and the consecration of the new synagogue was scheduled for Tuesday, 22 August, 1858.

The building was consecrated by Dr Adler, the Chief Rabbi, and had cost £700, the equivalent today of £86,000. Key donors were Sir David Salomons, Baron Rothschild and Sir Moses Montefiore, all prominent Victorian Jews. These were notable figures indeed for the humble Wolverhampton synagogue.

“Though comparatively small in its proportions, [it] is nevertheless sufficiently commodious for the congregation that will worship therein. [The interior] contains galleries, in which as well as in the body of the edifice, are convenient pews. At the top of the synagogue, against the wall, is the Ark, in which will be kept the Rolls of the Law.”

The Wolverhampton Chronicle

Growing Pains

There is very little to report on the building over the next decade, although the congregation itself found itself unable to pay on a number of occasions during the 1860s. By the 1870s, however, the congregation had begun to expand. In 1874, it was reported in the Jewish Chronicle that “owing to the rapid increase of the Jewish community at Wolverhampton, the necessity of a new and more spacious synagogue had been prominently brought under notice during the last holydays.”

By the 1880s, all of the founding pioneers had either died out, or moved away. The focus of the community’s work and finance turned to the burial ground. A series of appeals were made to enlarge it, surround it with walls and build an Ohel (prayer room). The appeals ran between 1884 and 1885 and the stone at the burial ground is marked 1884. The burial ground has remained largely the same way since this date.

The “Fire Mystery”

It is not until 1895 that we find a report of real note, when it is announced that the Wolverhampton synagogue will reopen. Major work has been undertaken with the old roof having been removed. The walls had been raised by three feet and a new roof of Bangor slate, underlined with Willesden paper, had been constructed. In 1896, the synagogue was once again closed, this time for “painting and re-decoration”.

The period around the turn of century has always been told as one where a fire damaged the building in 1902, forcing a rebuild in 1903. I could find no records of such an event recorded in newspapers, both Jewish and local. Upon further enquiry, it became apparent that this “fact” was based on local legend. I became even more suspicious of this information after hosting a series of talks at the building in late 2019. Paul Hooper, of the present occupier, St Silas Church, mentioned that during the restoration and conversion work of the mid 2000s, they discovered fire damage under the floor. This of course begged the question, ’how could a building that was rebuilt due to fire still have fire damage under the floor?’ The answer came from the most unlikely of sources.

It Pays to Look Everywhere

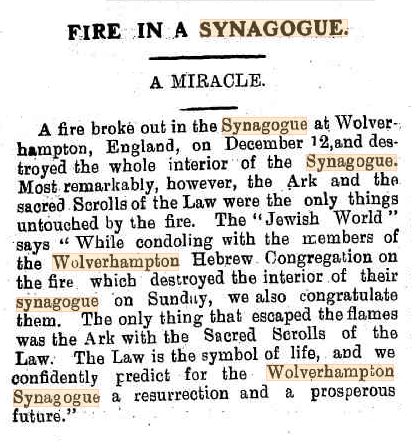

The Australian library has an online catalogue called Trove, which contains an article from the Hebrew Standard of Australasia. It detailed the following: On December 12, 1909, a fire broke out which destroyed the whole of the interior of the Synagogue. It is said that the only thing that survived was “the Ark with the Sacred Scrolls of the Law” and was titled, “a miracle”. By 1910, the Jewish Chronicle states that the annual meeting of the Hebrew Philanthropic Society was held at a temporary synagogue. The former Wolverhampton Synagogue at St James’ Square was still owned by a Jewish family, so this was almost certainly put into use.

But if the fire was in 1909, what caused the rebuild in 1903? The date above the door clearly states this date, and plans exist in the City Archives. The evidence is across various editions of the Jewish Chronicle, dating back to 1901. An “earnest appeal” is printed, stating that the Synagogue has been condemned as unsafe for public worship. It states that the cost of repairs is estimated at £600, the equivalent of £74,000 in today’s money. It is unclear what exactly had caused it to be condemned, but it is perhaps no coincidence that work took place to repair it just 6 years prior. Did this cause it to be structurally unsound, or to leak perhaps? I will concede that it is possible a fire could have caused it to be condemned, but surely there would be some sort of newspaper record of the event?

The Wolverhampton synagogue reopened in 1904, although the JC noted that it had only been closed for “several months”. The exterior of the synagogue is said to be “very pleasing” and made of Kingswinford brick with York stone dressing. The interior was described as “light and attractive”; panelled out and enameled in cream with gold detail. The pillars raising the gallery were green and gold, with the pews and remaining woodwork made of oak. Additionally, electricity had been added to the building and a Mikvah (women’s bathing room) and other accommodation had been added in the basement.

Later Years

The building would go on to be a synagogue for 90 years following the fire of 1909, before the small size of the community was such that a quorum could no longer be formed. The building was eventually converted into a church, and is now held as a place of worship by St Silas Church of England (Continuing).

Last year, I gave a series of talks at the building and it was wonderful seeing people recall bar mitzvahs and other events. I continue to research this topic and I am happy to give further talks on the subject. I can be contacted via enquiries@museumofwvandss.org.

Sources Used:

The Jewish Chronicle and Hebrew Observer; various, 1841-1910

The Hebrew Standard of Australasia, 21 January, 1910

The Staffordshire Advertiser, 26 August, 1858

Further Reading

- Get in touch with the synagogue’s present owners at the St Silas Church website.

- Learn about Wolverhampton’s Great Georgian era folly via this link.

- Learn about what Irish visitors thought of the area and its people at this link.