In recent times there has been much talk of erecting monuments to historic British figures from a minority background. In Wolverhampton, a plaque to a very worthy recipient fitting this criteria; former slave-turned-entrepreneur, George John Scipio Africanus, is soon to be unveiled by the Wolverhampton Society. What the people of the City seemed to have missed though is the hero from a minority background hiding in plain sight for over a century. This is the untold story of Douglas Morris Harris.

Different Paths, Same Destination

Leopold and Mabel Harris were not natives of Wolverhampton. Leopold was born in St Pancras, London and his wife was born a few miles away in Rotherhithe. Whilst they were born in the same place, they would not meet for another two decades, by which point Leopold had embarked upon a career in sales. At the time of the 1891 census, Leopold can be found boarding at 29 Warwick Row in Coventry. Despite being only 23, Leopold was already relatively successful in life, working as a manager at one of the city’s watch manufacturers.

Mabel Harriet Margaret Gardner shared similarities with Leopold in terms of moving around the country, and also spent part of her life in Australia. In the case of Leopold his transitory nature was due to his work in sales, whereas Mabel’s was related to her father’s employment as a vicar. By the early 1890s, however, their travels would bring these two natives of London back together.

Mabel and Leopold would marry in 1894 in Coventry. The couple would have three children; Irene, Doris and Gerald, before Leopold’s work took him elsewhere.

The Birth of a Hero

Douglas Morris Harris was born on 7 April 1898 in the St Paul’s district of Penn, Wolverhampton. At the time, his family lived at 49 Penn Road, the main artery into Wolverhampton from Stourbridge. His father, would spend time away from the family as part of his new job as a Commerical Traveller.

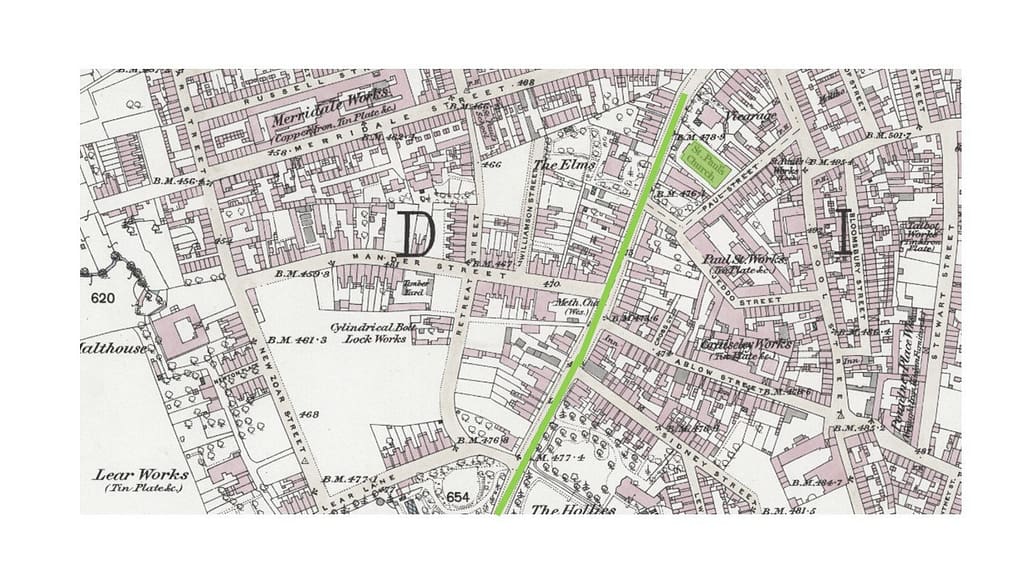

The Harris family would go on to have twins, Muriel and Olive, in 1902, and the family of 8 would live a comfortable life, aided by 2 servants. By 1911, Leopold had gained new employment, working as a Sales Manager for a local ‘Motor Fittings’ business. The growing amount of transport companies in the area had clearly served the Morris family well and they had moved to what would have been a new property at the time, 42 Lea Road (shown as Lear Lane on the 1885 map above).

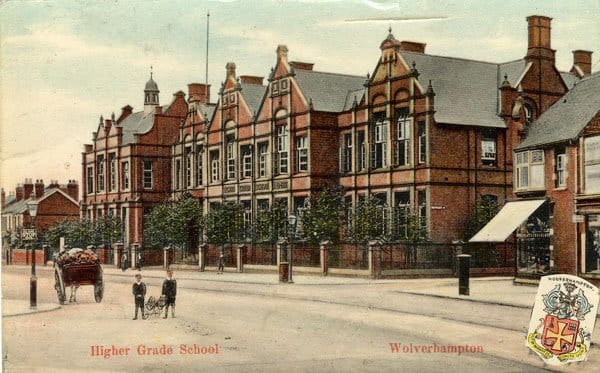

Douglas Morris Harris would attend the Wolverhampton Higher Grade School as a young man, a building which still remains to this day as the Newhampton Arts Centre. Following the completion of his schooling he began working for the Corporation Electricity Works.

The Outbreak of War

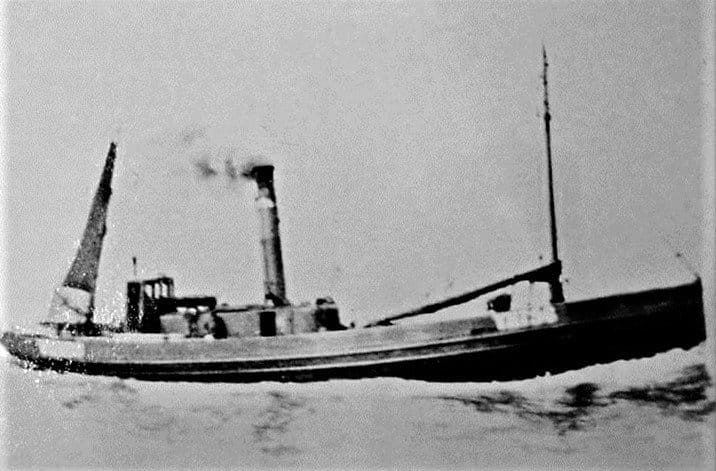

At the outbreak of World War One in July 1914, Douglas was still too young to sign up for the war effort and had to wait until he turned 18 before joining the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve (RNVR). Initially he served on HMS Admirable, before being transferred to the drifter HM Trawler, Floandi. This latter ship formed part of the Otranto Barrage – a line of ships which formed a blockade between the heel of Italy to the coast of Albania. The intent behind this was to control access to the Adriatic sea, and it was the job of drifters to form the blockade.

Douglas’ ship, Floandi, was built in 1914 and registered in Great Yarmouth. Along with other trawlers, anti-submarine nets placed between them were designed to stop attacks from German u-boats. To be effective at this, they also needed to be supplemented with aircraft and destroyers, but unfortunately, they were not. Rear Admiral, Mark Kerr, Commander of the British Adriatic Squadron, was unable to convince the Admiralty or Britain’s allies to supply this necessary support. The Barrage was therefore that in name only, and u-boats were easily able to slip through.

Douglas Morris Harris’ Final Act

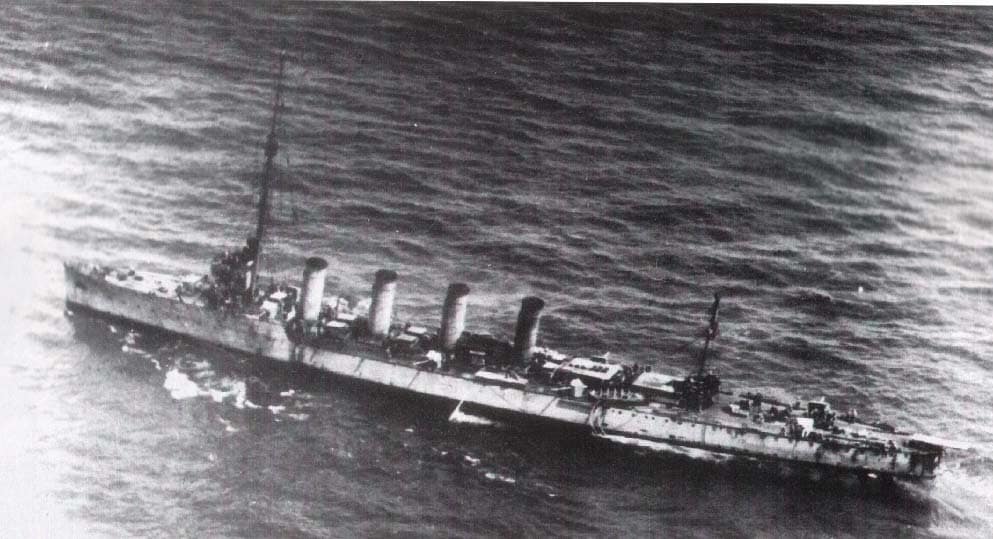

On the night of 14-15 May, 1917, the Battle of the Otranto Barrage began. At 03:30, the line of drifters came under heavy attack by three light cruisers from the Austrian Navy; SMS Helgoland, SMS Novara and SMS Saida. Initially, the cruisers sailed parallel to the barrage, and in the half light the drifter crews assumed them to be Allied warships. Shortly thereafter, the Saida opened fire on 4 of the 5 drifters, followed by the Helgoland attacking the drifters at the Western end.

After being ordered to surrender by the Helgoland, skipper of the drifter Gowanlea, Joe Watt, opened fire, before attempting to ram the boat. The mere 6 pound guns of the Gowanlea were dwarfed by the heavy shells of the Helgoland. Despite this, Lee only abandoned ship after the Gowanlea became riddled with shell holes. He was subsequently awarded the Victoria Cross for his actions.

At 04:00, the Novara attacked, causing a series of 12 direct hits on the Floandi. Able Seaman Douglas Morris Harris refused to leave his post, operating his wireless throughout. He continued to send messages asking for assistance until shrapnel from one of the 12 hits caused his death. Somehow, the Floandi remained afloat, despite the death of Able Seaman Harris and 5 of his colleagues. The attack on the barrage did not cease until 05:37, whereupon the Austrians were chased back to Montenegro by the arrival of HMS Bristol and HMS Dartmouth. This battle would continue to rage until the early afternoon, whereupon both fleets dispersed due to their losses.

The Aftermath

The Battle of the Otranto Barrage would prove to be the largest naval confrontation in the Adriatic throughout World War One. The battle was hailed as a great victory by Austria-Hungary and a “rout” for the Allies. In total, the small group of 5 Austrian ships had resulted in the capture of 72 Allied personnel and destroyed:

- 47 Drifters

- One Destroyer

- One Munitions Ship

Whilst the battle was seen by Austria-Hungary as a great victory, it did not change the war in terms of strategy. It did prove, however, to be highly embarrassing for the Royal Navy and this may shed some light onto the actions that occurred thereafter.

The Finger of Blame

Rear Admiral Mark Kerr submitted a list of 119 drifter crew to receive exceptional bravery awards, on 21 May 1917. The response to his request was anything but brave. The Naval Secretary, Allan Everett, stated the list needed to be cut by two thirds. In addition, the Sea Lords argued that the largely co-opted civilian drifter crew should have put up sterner resistance during the ‘rout’. Douglas Morris Harris did not make the cut. Rear Admiral Kerr would later write that ‘fourteen drifters were sunk and several lives sacrificed on the altar of parochialism‘.

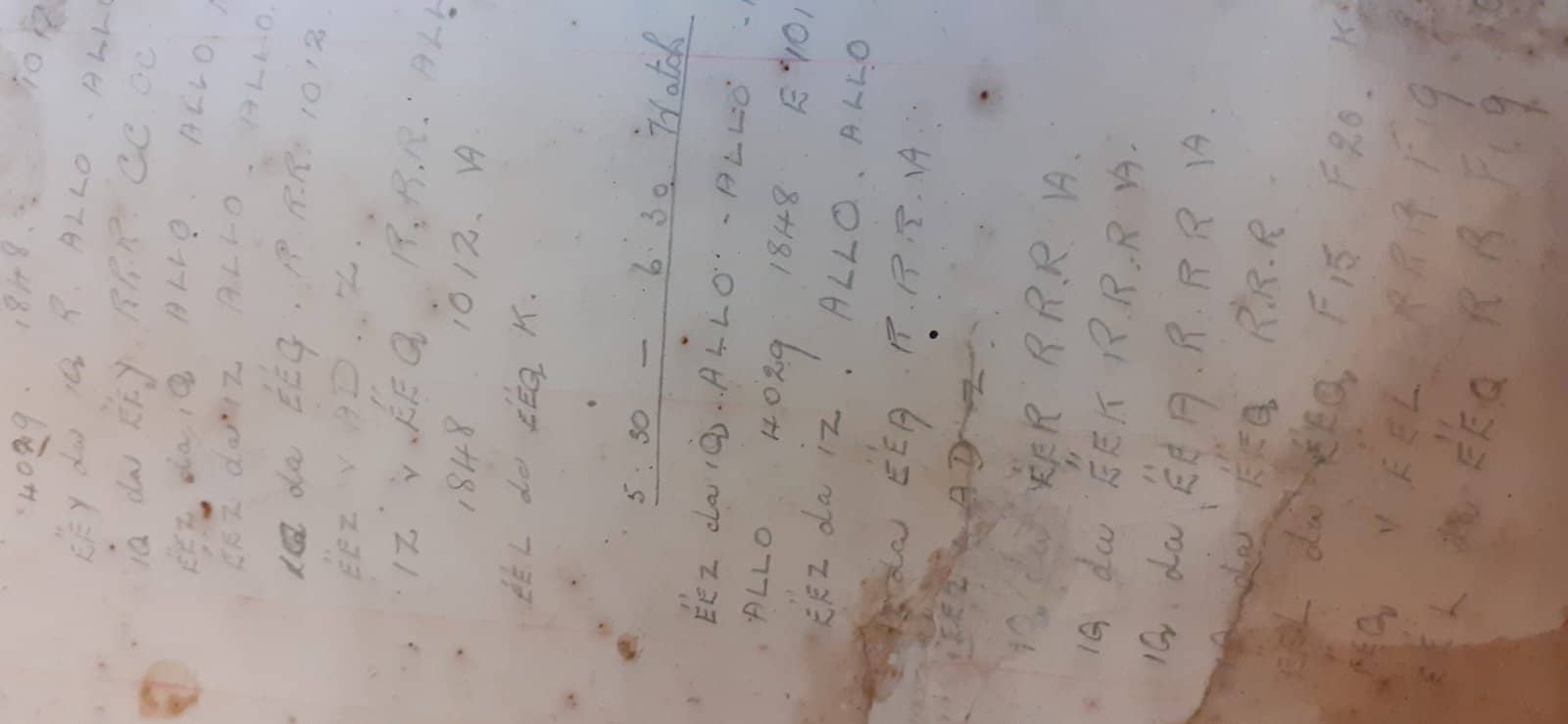

Undettered, Kerr proposed that Douglas’ telegraph log, recovered from the Floandi, be deposited in the newly-founded Imperial War Museum.

“[Harris had] continued to send and receive messages, although the drifter was being riddled by shells, until he was killed by a piece of shrapnel whilst writing in the log. The piece of shell perforate the log, and the line made by his pencil when he was hit and collapsed can be seen on the page upon which he was writing. The operator was found dead in his chair, lying over the log.”

The Birmingham Post, 21 July, 1917

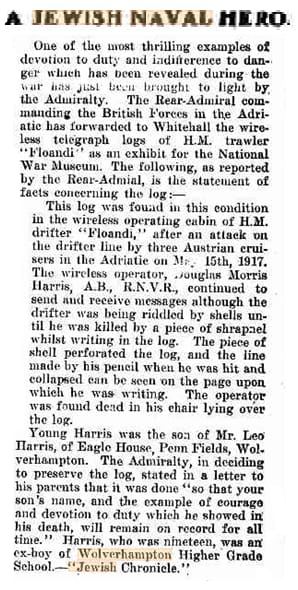

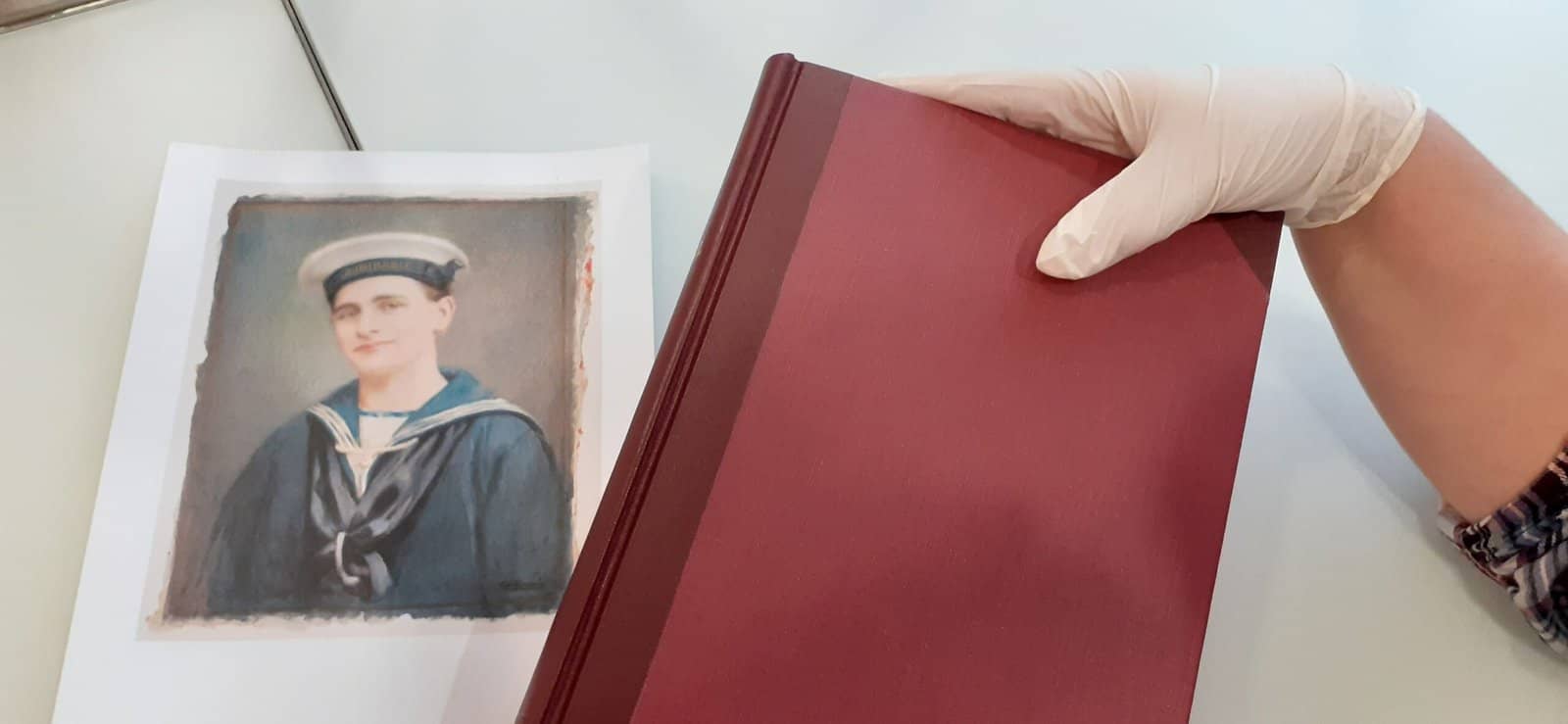

Both the log book and George Phoenix’s portrait of the “young hero” were exhibited in Wolverhampton before being given to the Imperial War Museum. Both can be seen in the images above (courtesy of Quintin Watt).

The articles were displayed at Wolverhampton Art Gallery over the Bank Holiday weekend of 1917, 4-6 August. Visitors queued to form past it, similar to how people visited Queen Elizabeth II Lying-In-State. More than 1,000 visitors attended on Sunday, with a further 5,732 attending on Bank Holiday Monday. “Correspondingly large numbers of visitors” attended during the remainder of the week. To put this number into context, the entire population of Wolverhampton in 1901 was only 95,000.

Honouring Douglas Morris Harris

Douglas’ bravery prompted a campaign for a memorial to honour the young man, and at the end of July 1917, contributions stood at £120, the equivalent of around £10,500. By 1918, the logbook and portrait had moved to Burlington House, the temporary home of the War Museum. Several weeks later, the a design by Robert Jackson Emerson was selected for the Harris memorial. A model and photograph were submitted to Wolverhampotn Council’s Parks and Baths Committee on the final day of 1917. The proposal requested the memorial feature “within the open space in Lichfield Street adjacent to the Art Gallery“.

The memorial to Douglas Morris Harris was unveiled on Sunday, 23 June 1918 before a crowd of thousands. Hundreds more were said to have “looked down from every window that happened to command a view of the grounds“. Harris’ former commander, Rear Admiral Mark Kerr, lead the service, and a guard of honour was provided by the 4th Battalion Staffordshire Volunteer Regiment. Music was provided by the Police Band.

Part of Rear Admiral Kerr’s eulogy to Able Seaman Douglas Morris Harris.“These memorials are of great value, and this one shows that Wolverhampton is going to keep alive the memory of duty nobly done, in the hearts and minds of its children and their children’s children.”

A Hidden Identity

So what of the “hidden identity” of Douglas Morris Harris? Well, in researching the hidden history of Wolverhampton’s former synagogue, a second interesting story came up from an Australian newspaper.

The story, found in the 28 September 1917 edition of The Hebrew Standard of Australasia, confirmed that Morris was, in fact, Jewish. Upon further analysis, records can be found of the bar mitzvah of Douglas’ brother, Gerald, at the Wolverhampton Synagogue. Upon looking into Leopold’s family tree, he was the son of Morris Hart Harris, who was descended from a line of Cornish Jewry. The line can be traced back to Germanic Europe in the early 1700s. What is particularly interesting however, is that Douglas’ mother can trace her ancestry back through several Christinan vicars. Perhaps it is this that has meant his Jewish ancestry has largely been forgotten over the years.

Regardless of why Douglas’ identity has been lost over the last century, it is time to celebrate it. Had he held a weapon and not a pencil, he would almost certainly have received a medal for bravery, perhaps even the Victoria Cross itself. In an age where (rightly), there is a clamour for representation in historical statues and tributes, Wolverhampton can be proud that it has had one for over a century, hiding in plain sight.

As our organisation continues to grow, Harris’ logbook is certainly something which would be a fitting exhibit for Wolverhampton. We certainly hope that one day it could pay a visit home, at least temporarily. Thank you for your courage and sacrifice, Douglas, may your deeds never be forgotten by the City of Wolverhampton.

Sources and Further Reading

- Wolverhampton’s Great War, 1914 – 1921, Quintin Watt

- The Hebrew Standard of Australasia, 28 September 1917

- Wolverhampton’s War

If you’d like to learn more about Wolverhampton in World War One, you can purchase a copy of ‘Wolverhampton’s Great War, 1914 – 1921’ via Amazon by following this link.

Thank you very much for this post. It is wonderful reading. One of my relatives, Dennis Nichols, was skipper of Floandi and Chief Skipper of that flotilla of drifters. The Admiralty actually did far worse than leave the names of heroes off the awards recommendations; they got it factually wrong. The Gowanlea was not actually part of the flotilla attacked by the cruisers. The story quoted was that of Floandi and unfortunately a mistake was made at Admiralty and the wrong name was substituted on the VC recommendation. When he was notified of the award, Rear Admiral Kerr (I believe but could have been the Commander – yet to evidence) tried to correct the error but was told nothing could be done as the recommendation was already on the desk of the king.

Comments are closed.